Carine van Rhijn writes…

Lizard shampoo?[1]

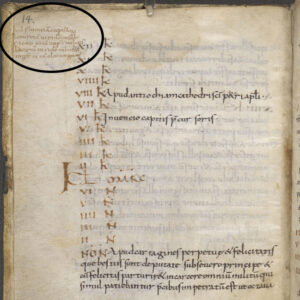

The manuscript of this month, London BL Add 19725, is not medical at all.[2] Its first 87 folia (including four which were added at the beginning of the codex) form a pastoral compendium filled with texts useful for a local priests (or, perhaps more likely, for somebody training to become one) while the remainder of the manuscript (f.88-127) is filled with saint’s lives. Bischoff dates it to the late ninth century and thinks its most likely place of origin is in an area ‘influenced by the Rheims style’.[3] Not too long after its composition, the manuscript moved to the Tegernsee-area in the South of Germany, where it received a series of additions.

What makes this manuscript interesting for us is the fact that most of these additions, written by several hands, are medical and unrelated to the main contents of the book.[4] On f.37v, for instance, we find a recipe against a sore throat, while f.41r (in the margin of the bestiality-chapter of a penitential, probably for mnemonic purposes) offers remedies for several animal diseases. The most surprising of the additions, however, appears in the margin of the martyrology.

It reads as follows:

Ad fluentiam capillorum.

Satureiam viridem cum sale

et aceto totum caput involuit.

Lacertam viridem combustam,

cinerem eius cum oleo unguatur.

For flowing hair.

Cover the whole head

with fresh summer savory and salt

and vinegar. [Then] rub it with

the ashes of a burnt green lizard, mixed with oil.

At first sight, this looks much like a recipe for a shampoo or conditioner, where the head is first thoroughly cleaned (salt and vinegar will disinfect and probably terminally discourage parasite life, summer savory adds a nice smell), after which a second – nurturing? – mixture of lizard ashes and oil are applied.

Where the scribe found this recipe is a mystery, as is the ultimate source for this piece of knowledge. It does not feature in any of the published late antique and early medieval recipe collections, although lizards were connected with the treatment of hair issues more often.[5] Why the scribe decided to keep it for posterity is, likewise, an open question, especially if Kerff is right that it was added in the monastery of Tegernsee – a male monastery with tonsured inhabitants.[6]

London BL Add 19725 f.8v.

Even if this exact recipe does not feature in any medical collection (as far as we know at present, though a significant number of early medieval recipe collections remain unedited), we do find recipes with a similar title. Hair was an important theme: recipe collections contain all kinds of hair-related material such as remedies for too much or too little hair, hair in the wrong places, hair of the wrong colour, but also less appetizing problems. One recipe with nearly the same title (Ad fluentes capillos) features in Marcellus of Bordeaux’s De medicamentis liber (dated ca. 400) among treatments for ailments such as mange, scurvy, scabies, baldness or hair loss through magic. Hair was clearly serious business to Marcellus – one of his remedies promises a full head of hair plus a beard on bald men, and even on women.[7] If our lizard shampoo stems from a similar context, we should perhaps not interpret it as a hair-care product, but as a remedy for the more unpleasant problem of hair loss. Even though ‘fluere’ has as its first meanings ‘flowing’ (as do rivers, time, or rhetoric[8]), in Marcellus’ recipe it clearly refers to hair ‘flowing away’. The interesting thing about our solitary recipe in the London manuscript is that we cannot know how we should read it: on its own, without further context, its interpretation can go either way.

Possible candidates for lizard shampoo? left: Stuttgart Psalter, Badische Landesbibliothek cod.bibl.fol.23, f.149v; right: idem, f.127v.

[1] This blog is based on Carine van Rhijn ‘”Tangled knowledge”, or: how to interpret a recipe for a lizard hair mixture in an early medieval pastoral manual’, in: Martin Mulsow ed., Das Haar als Argument. Zur Wissensgeschichte von Bärten, Frisuren und Perücken, Gothaer Forschungen zur Frühen Neuzeit 21 (Stuttgart, 2022), pp. 17-28.

[2] As a result of the cyber-attack, the manuscript and its description are at the moment unavailable on the British Library website. The image is a screenshot made some years ago.

[3] Bernhard Bischoff, Katalog der festländischen Handschriften des neunten Jahrhunderts (mit Ausnahme der Wisigotischen) vol. I: Aachen-Lambach (Wiesbaden, 1998), no 2379 and 2380.

[4] First published by Franz Kerff, ‘Frühmittelalterlichte pharmazeutische Rezepte aus dem Kloster Tegernsee’, Südhofsf Archiv 67 (1983), pp. 111-16; a fuller study (and more complete transcription) can be found in Ria Paroubek-Groenewoud, ‘Transfer of medical knowledge in the early middle ages. Medical texts in the margins of a ninth-century non-medical manuscript (London BL Add 19725)’, Unpublished RMA-thesis, Utrecht University 2019.

[5] Pliny, Naturae Historiae, ed. Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff (Leipzig, 1906), book 29, c.28.

[6] Kerff, ‘Frühmittelalterlichte pharmazeutische Rezepte’, p.111.

[7] Marcellus of Bordeaux. De medicamentis liber. Edited by Eduard Liechtenhan and Maximilian Niedermann. Translated by Jutta Kollesch and Diethard Nickel. CML 5, 2 vols. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1968. The chapter that deals with hair concerns (6) is on pp. 94-101.

[8] See the Brepolis Database of Latin Dictionaries (DLD) under ‘fluo’, ‘fluere’ and ‘fluentia’.